Every spring, my boys and I order a small cup of five tiny caterpillars to watch as they eventually become butterflies. The caterpillars are contained in a cup with some resin-like food for them to munch on for about two weeks. Then they crawl to the lid of the cup, hang upside down, and form their chrysalides.

Once each chrysalis has hardened, the lid can be removed and placed inside a butterfly net. After another two weeks, the chrysalis will hatch and out pops a beautiful monarch butterfly! We usually keep them in the net for a few days, watching them munch on small pieces of fruit and adjust to their wings before we release them in the back yard.

The boys really enjoy watching the whole process, especially when we release them, but let’s be honest, I get more excited about it than they do. Every time. We usually place the cup of caterpillars and the butterfly net on the counter right above the sink. So, I get to watch their activity every day (since there are always dishes to clean, somehow). And I find the process of metamorphosis fascinating.

One of the years we were growing our little caterpillars, I noticed one in particular as it began to hatch out of its chrysalis. It pushed half way out, and then it stopped. Its wings were still folded, and it still had a piece of chrysalis stuck to the top of its head. Yet it just sat there.

The next day, it crawled the rest of the way out of its chrysalis. However, its wings had dried in that crumpled, folded-up position. And the small chunk of chrysalis was still stuck to its head. It was clear when we released this poor little guy, he wasn’t going to be flying off into the sunset. He was going to be bird food.

It made me realize how critical the process of metamorphosis is to the success of an entire species of organisms. There is this dramatic and total change from one type of organism into a completely different type of organism. The tadpole becomes the frog, the caterpillar becomes the butterfly, the grub becomes the beetle, and the maggot becomes the fly. But how and why does that happen?

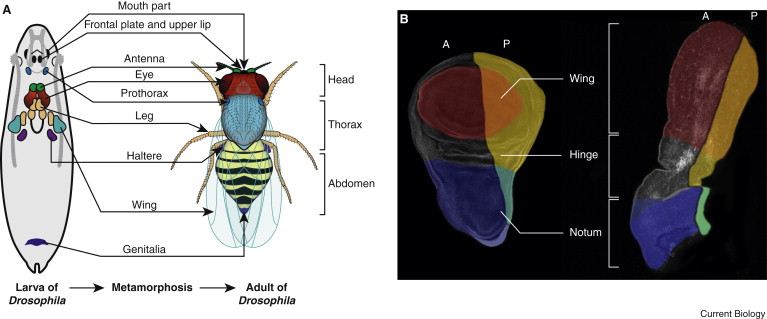

Although there are different types of metamorphosis, these are all examples of insects that undergo complete metamorphosis, known as “holometabolous” (from the word “holo” meaning “total”). In these cases, the adult form is completely different from the larvae – the body structure, mode of transportation, diet, feeding mechanisms, and habitats.

All of those things must change completely – and perfectly – for the new organism to survive. When something goes wrong – like that butterfly with the crumpled wings – the new organism doesn’t live to reproduce. In other words, a species does not have multiple generations to improve on the process of metamorphosis to get it right. The first generation of the organism must perfectly execute metamorphosis or there is no second generation.

How does the process of metamorphosis work?

For the caterpillar, it enters the pupa stage once it has formed the chrysalis. While tucked inside the chrysalis, digestive enzymes break down the cellular structure of the caterpillar into almost an insect soup. Thus, the chrysalis not only protects the insect during metamorphosis but contains the liquid mess of broken-down caterpillar cells.

The only thing not dissolved are the imaginal discs. These specialized cells replicate to produce specific adult insect structures. There are imaginal discs that form the head, wings, antenna, legs, and other body organs for the adult form of the insect. Once each imaginal disc type has replicated to produce its adult structure, they are fused together to complete the adult insect. Then the butterfly hatches from its chrysalis.

Amazingly, the insect develops these imaginal discs while still in the embryonic stage. It carries them through the larval and pupal stages until they are used to complete the metamorphosis to the new adult stage. These discs essentially create an entirely new organism from decomposed larval cell parts.

How did this process of metamorphosis arise?

Darwinian evolutionists claim the first insects on earth did not go through metamorphosis. Instead, a fully-formed miniature adult would hatch from the eggs. Evolutionists believe around 280 million years ago some insects began to hatch in forms that neither looked nor behaved like their adult versions.

Why would that happen? Darwinists point out that the metamorphosis of insects could help increase the insect population. When the adult and its offspring are not competing for the same food and space, there are more resources available to support a larger population.

For example, with mammals, the adults eat the same food as the offspring, which leads to competition within the species. But when the baby caterpillar is feasting on leaves and the adult butterfly is flying to flowers for nectar, they are not competing for the same resources. Darwinists say this allows more of this population to live in the same space since the adult and offspring are not in competition.

Though that may be a benefit to species that undergo metamorphosis, it doesn’t explain the origin of this intricate process of metamorphosis. The butterfly can’t decide to produce offspring that feed on something different in order to have less competition over food and then evolve to make that happen. Evolution cannot plan ahead, and then mutate what it needs to improve the species. Evolution must be driven by blind, random genetic micro-mutations.

Therefore, a genetic mutation must occur to give the caterpillar, while in its embryonic stage, the imaginal discs necessary to form butterfly wings, heads, antennae, feeding mechanisms, and reproductive organs – things a caterpillar literally has no used for unless it were going through metamorphosis. In other words, evolution would have to plan ahead – but evolution does not do that.

Not only does it need to plan ahead for the body structures to live as a butterfly, the caterpillar would also need a mutation to gain the ability to form a chrysalis. The caterpillar needs digestive enzymes to break down its cellular state as a caterpillar so that it can be “rebuilt” as a butterfly. Then there must be something that fuses these new butterfly body structures together so it is a complete organism.

For Darwinian evolution to explain this process, each of those features would need to be the result of a separate and random micro-mutation. However, getting those features one at time would not result in a successful metamorphosis. Acquiring the digestive enzymes without the ability to form a chrysalis leaves the caterpillar never changing to the butterfly.

What if the caterpillar can make its chrysalis but doesn’t have any digestive enzymes to break down the caterpillar body structure? It becomes a trapped, dead caterpillar. What if it lacks the ability to fuse the separate butterfly body structures together? If the first generation of metamorphosizing caterpillars only had imaginal discs to form wings but didn’t have the imaginal discs for the other butterfly structures, then it won’t live as either a caterpillar or a butterfly.

If the caterpillar does not have a genetic mutation that provides for all of those things at the same time in the same generation, it cannot successfully change into a butterfly that could fly and reproduce. It needs all of those features present at the same time for metamorphosis to work. However, gaining all of those features en bloc would not be the slight, successive modifications that Darwinian evolution requires. It would look more like a unique creative event.

While some sources describe this process as “evolving,” even the language used to describe this process paints a different picture. One biology website [1] describes the imaginal discs as having “precise positional information.” The discs generate subdivisions or compartments so that each type of cell is restricted to a certain area where it can replicate. And the cells cannot mix across cell type while these discs are growing.

The article even refers to levels of “organization” and how these restricted compartments are considered “organizing centers” that ultimately form a “prepattern” of the adult body structure for the organism being produced at the end of metamorphosis. When things need information and organization and planning, we know there must be something besides a blind, random, natural process responsible for it. Information, order, and planning requires an intelligent source. Darwinian evolution cannot account for such a process as this.

In addition, this isn’t a process that can be developed by trial and error. It must work right the first time or the caterpillar dies. It would never have the chance to reproduce as a butterfly, which brings up an interesting point about caterpillars – they have no means of reproducing. The caterpillar’s reproductive organs do not develop until it is inside its chrysalis, when it is becoming a butterfly. Reproductive organs would be useless on a caterpillar.

What does all this mean?

Ultimately, the butterfly cannot decide there would be less competition for space and food if its offspring were a different type of organism, and thus make a change. According to Darwinian evolution, the butterfly producing a different type of organism as its offspring must be the result of a series of blind, random genetic mutations working slowly over a long period of time.

If it is true that butterflies originally laid eggs that hatched out miniature butterflies, then there are a lot of random, genetic mutations that must take place for the butterfly to now lay eggs that hatch out caterpillar larvae that go through metamorphosis. Instead of developing a butterfly embryo, the butterfly must develop a caterpillar larva.

But the caterpillar larva has a different body plan, different feeding mechanisms, different habitat, and no reproductive system. In addition, the caterpillar larva must have the structures and blueprints (those imaginal discs) embedded within it so it can later become a butterfly, along with the ability to form a chrysalis and break down the caterpillar structure to a cellular level. Those differences could not arise from one micro-mutation at a time and still result in a viable offspring. Darwinian evolution cannot successfully generate this kind of change through random genetic micro-mutations.

All of those features must be present at the same time in order for the transition from caterpillar to butterfly to be successful. As my boys and I observed, if you have the slightest error in that metamorphosis process, you don’t produce a viable butterfly that can live to reproduce. Instead, you produce an evolutionary dead-end.

2 thoughts on “How Does the Caterpillar Really Become a Butterfly?”

What a God Designer we serve! I was thinking too how this amazing process is a little bit analogous to the process of being born again in Christ.

Great analogy!! We are to put off the old self and put on the new — just like that caterpillar must destroy his old self and put on the new body of the butterfly! That’s an excellent analogy!

Comments are closed.